Katharine Hayhoe explains how political and religious views can shape understanding of climate change and the world

“Wildfires, Once Confined to a Season, Burn Earlier and Longer,” “Sierra Nevada Snow Won’t End California’s Thirst” and “Climate-Related Death of Coral Around World Alarms Scientists” were all April headlines concerning critical and foreboding aspects of climate change from the New York Times.

However, despite the reputable stories and claims in these articles, as well as others, denial of climate change is still prevalent in the United States. In fact, a 2014 study conducted by the Pew Research Center found that only four-in-ten Americans classified global climate change as a major threat to their nation “making Americans among the least concerned about the issue.”

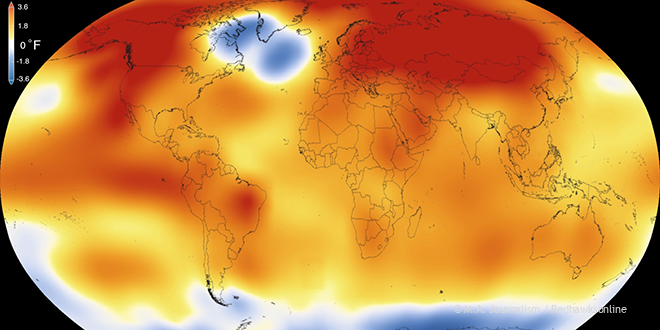

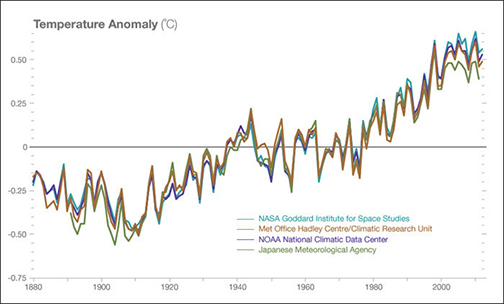

“Study after study has found that [the vast majority] of scientists agree not only that climate is changing but that humans are the main cause,” said Katharine Hayhoe, director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech University, during an April 21 interview on Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) before coming to speak at Minnehaha Academy.

“Study after study has found that [the vast majority] of scientists agree not only that climate is changing but that humans are the main cause,” said Katharine Hayhoe, director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech University, during an April 21 interview on Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) before coming to speak at Minnehaha Academy.

However, despite the overall consensus of the scientific community, the American population remains divided over the causes and existence of climate change. Hayhoe states that, despite the correlations seen between religious affiliation and denial of climate change, religion affiliation is not a causation of climate change denial but correlates with political affiliation which is the true cause.

Additionally, Hayhoe, who was named one of Time magazine’s top 100 most influential people and Christianity Today‘s 50 women you should know, states that even when the religious groups that have the greatest percentage of climate change denial such as Catholics and Evangelicals are broken down, climate change denial is divided by liberal and conservative groups within those religious sect.

“When we look at all of the different factors that determine our opinions of climate change, there is one factor that is the number one predictor of what we think about climate change,” said Hayhoe. “It’s not religion. It’s not where we sit on a Sunday. It’s where we fall on the political spectrum.”

Hayhoe states that the implications that politics have on our view of climate change is a direct relation. Thus, conservative values of smaller government, lower taxation on individuals and businesses and less government regulation of the economy directly influence attitudes toward climate change that many conservatives assume would increase government involvement and legislation in their communities, raise taxes on energy and create economic stressors for businesses to reform environmental policies.

These assumptions decrease the tendency of conservatives to say they believe in climate change even if they do because it’s socially unacceptable to recognize climate change as a global problem and refuse to take financial action due to more conservative economic and political views.

“If we are a Christian, especially a conservative Christian or an Evangelical, if we are Republican, if we live in the red states down the middle of the country we’ve been told that we can’t be who we are and care about climate change,” said Hayhoe. “The [people dismissive of climate change] are using fear to say ‘the government will come in and will set your thermostat and will dictate every aspect of your life.'”

However, since these beliefs are harder to justify when it comes to global issues, many people use religious authority or scientific data to back their claims against climate change.

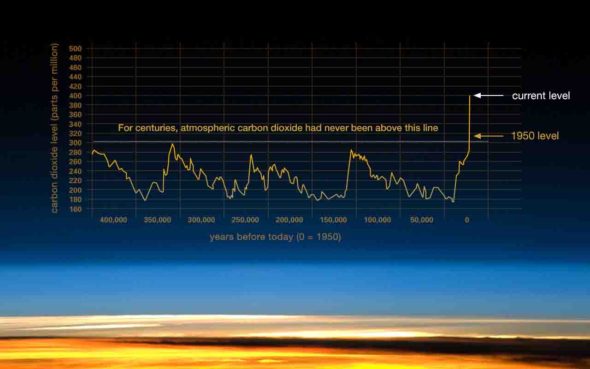

“One [reason people deny climate change] is just a lack of understanding of the science behind it and of geologic time and Earth cycles,” said science teacher Sam Meyers. “Whenever you have fluctuating data, you can always take short-term trends out of context and say, ‘hey it’s doing this,’ but when you back up and look at the trend over decades or centuries or thousands of years, you can see it’s doing something different.”

Additionally, many people state that because of the lack of immediate effects that we encounter locally, climate change doesn’t exist or isn’t progressing fast enough to ever do us any serious permanent damage.

Yet, Meyers argues that “just because [climate change] isn’t affecting us right now, doesn’t mean it’s not going to or that it won’t just because it’s not extreme or im mediate.”

mediate.”

Meyers suggests that, in addition to the financial and economic impacts that make many people regard climate change as threat, the impact that it has on our lives may also not indicate the true severity of the situation.

Because of political and social implications, climate change can often be a sensitive topic to discuss.

However, Hayoe argues that uniting people by using common values, such as faith, we can overcome these divides to address the fundamental issue.

“The most important thing to do [when talking about climate change] is to end with solutions that are compatible with our values,” said Hayhoe.

“Solutions like investment in technology, conservation, growing the local economy. Solutions that people can buy into that aren’t branded as being from one side or the other of the political spectrum.”

Both Meyers and Hayhoe state that, although the political effects of climate change are an important topic in the conversation, we have to leave behind our affiliations when having these discussions.

“There are certainly opinions, and there are facts, and there’s faith, and there’s science,” stated Hayhoe. “They are not the same thing, we need them both, but whether we believe in the science or not is almost irrelevant to the consequences. It’s not irrelevant about deciding what to do about it, but it’s irrelevant to whether climate is changing.” It’s not about belief, she said. “One of the first things I say to people often is, ‘I don’t believe in global warming,’ because when we look at the definition of belief or faith, it is based on spiritual apprehension not physical proof. When we look at science, that’s looking at the physical world through observing and experimenting. So I don’t think climate change is something to believe in. I look at the data, I look at the information, I look at the facts, and it is the most logical conclusion.”

For more information, Prof. Hayhoe recommends the website Skeptical Science, which answers the most common questions people have about climate.